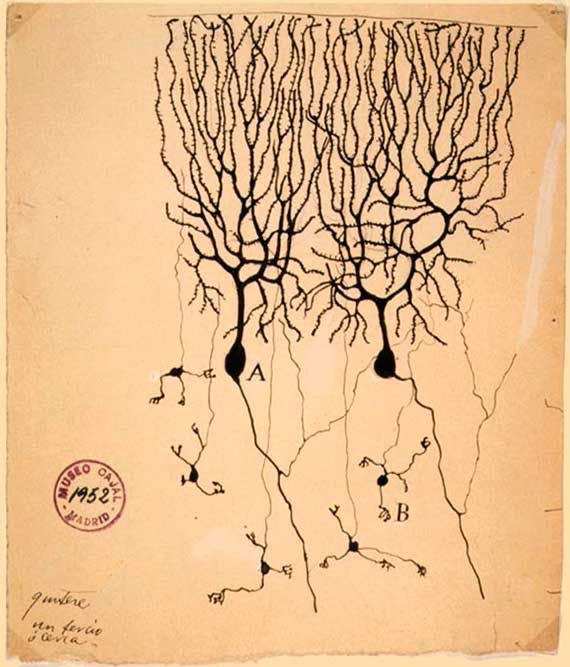

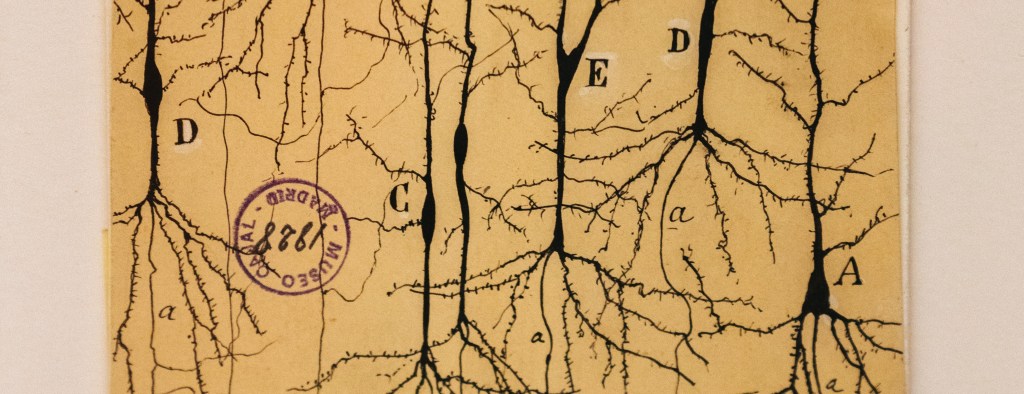

Drawings from Ramón y Cajal, Instituto Cajal CSIC

A picture is worth a thousand words. They drive passion, joy, tears, nostalgia, and some of them even make history. The same can also be said about photographs concerning science and technology. They not only capture emotions, but also reveal so much of the world around us that we don’t understand. Just like anyone who loves science and technology knows the significance of photographs, many scientific photographs have had an impact on me. With this short article, I would like to share some of those photographs from the world of science and technology that I love. This list of photos is not in any specific order except maybe partially based on my personal interest in them.

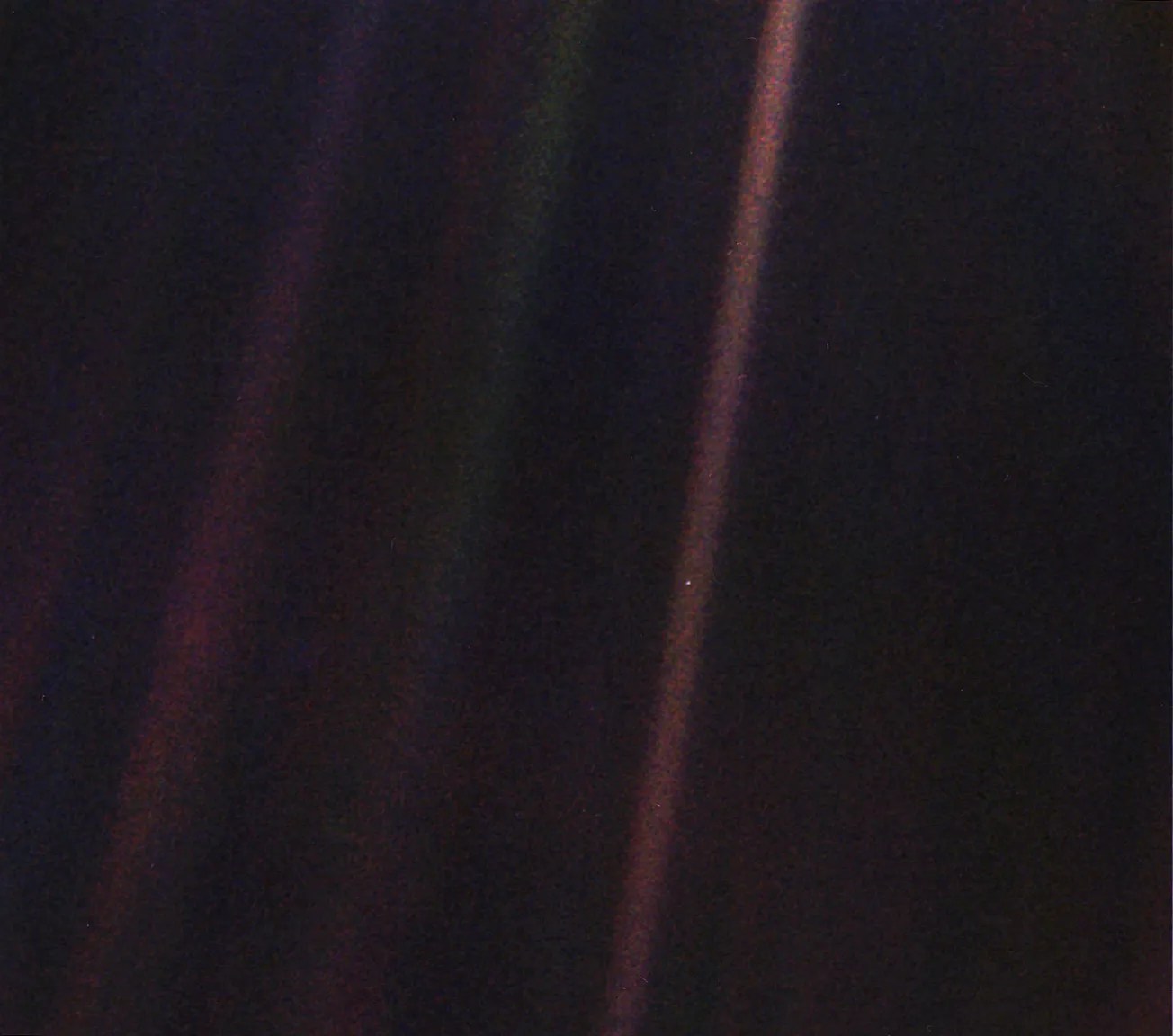

Pale Blue Dot

This photograph, called the ‘Pale Blue Dot’, was taken by NASA’s space probe Voyager 1 from about 6 billion km from the Earth in 1990 [1,2]. It shows our planet, the Earth, a tiny white-blue speck, just like a pixel, suspended in a beam of light. It was the idea of astronomer Carl Sagan to take this image knowing that from such a large distance the photograph will not show much. They wanted to show us our Earth’s vulnerability in the vast cosmic landscape.

I will only mention what Carl Sagan wrote about this photograph:

“From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it’s different. Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.“

– Carl Sagan, in his book also titled, Pale Blue Dot [3]

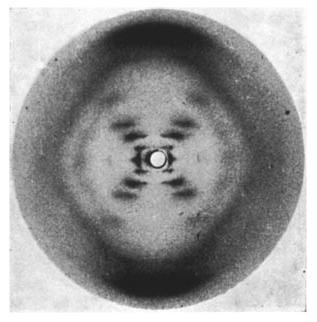

Photograph 51

This “Photo 51” is an X-ray diffraction image obtained by shooting DNA strands with beams of X-rays. This image was taken by Raymond Gosling under the supervision of Rosalind Franklin [4], and proved critical in unraveling the helical structure of the DNA. As Cobb et. al. write, “this image is treated as the philosopher’s stone of molecular biology, the key to the ‘secret of life’ (not to mention a Nobel prize).“[5].

To understand the structure of DNA, Franklin and Maurice Wilkins (co-supervisor of Gosling) were working on experiments with X-ray diffraction, while James Watson and Francis Crick were working on the theoretical modelling of DNA structure. Although these 2 teams were operating independently, “they linked up, confirming each other’s work from time to time, or wrestling over a common problem” as noted by Joan Bruce [5,10]. This experimental result (Photo 51), without the permission of Franklin, was shared by Wilkins with Watson and Crick. Later, Watson and Crick utilized the results from Photo 51 along with additional data and became the first ones to correctly propose the chemical model of DNA. The model proposed by Watson and Crick [6], along with papers by Wilkins and team [7], and by Franklin and Gosling [4] were published in the Nature Journal in 1953. Later in 1954, Francis and Crick published a full paper on this topic, where they also acknowledged that without Wilkin’s and Franklin’s data, “the formulation of our structure would have been most unlikely, if not impossible” [8], thereby recognizing the significance of Photo 51.

In 1962, Watson, Crick and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel prize in Medicine “for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material” [9]. Franklin had died 4 years earlier due to ovarian cancer and was not awarded the prize, although the rule against posthumous Nobel prize awards came into being only later in 1974. Similarly, the work by Gosling was not cited by the committee.

Footprint on the Moon

This well-known photograph is one those that inspired me as a kid to pursue science. It is one of the first footprints on the moon imaged by Apollo 11 astronaut Edwin Aldrin on 20th July 1969. [11,12]. The footprint was photographed as a part of an experiment to study the nature of lunar soil and the impact of pressure. More than the planned empirical intent of this photograph, it is an icon of human curiosity and its continuous perseverance towards understanding nature. The lunar landing was a remarkable achievement, as it took just 64 year for humans from learning how to fly – with Wright brothers’ first successful engine powered flight in 1903 [13] – to finally landing on moon in 1969.

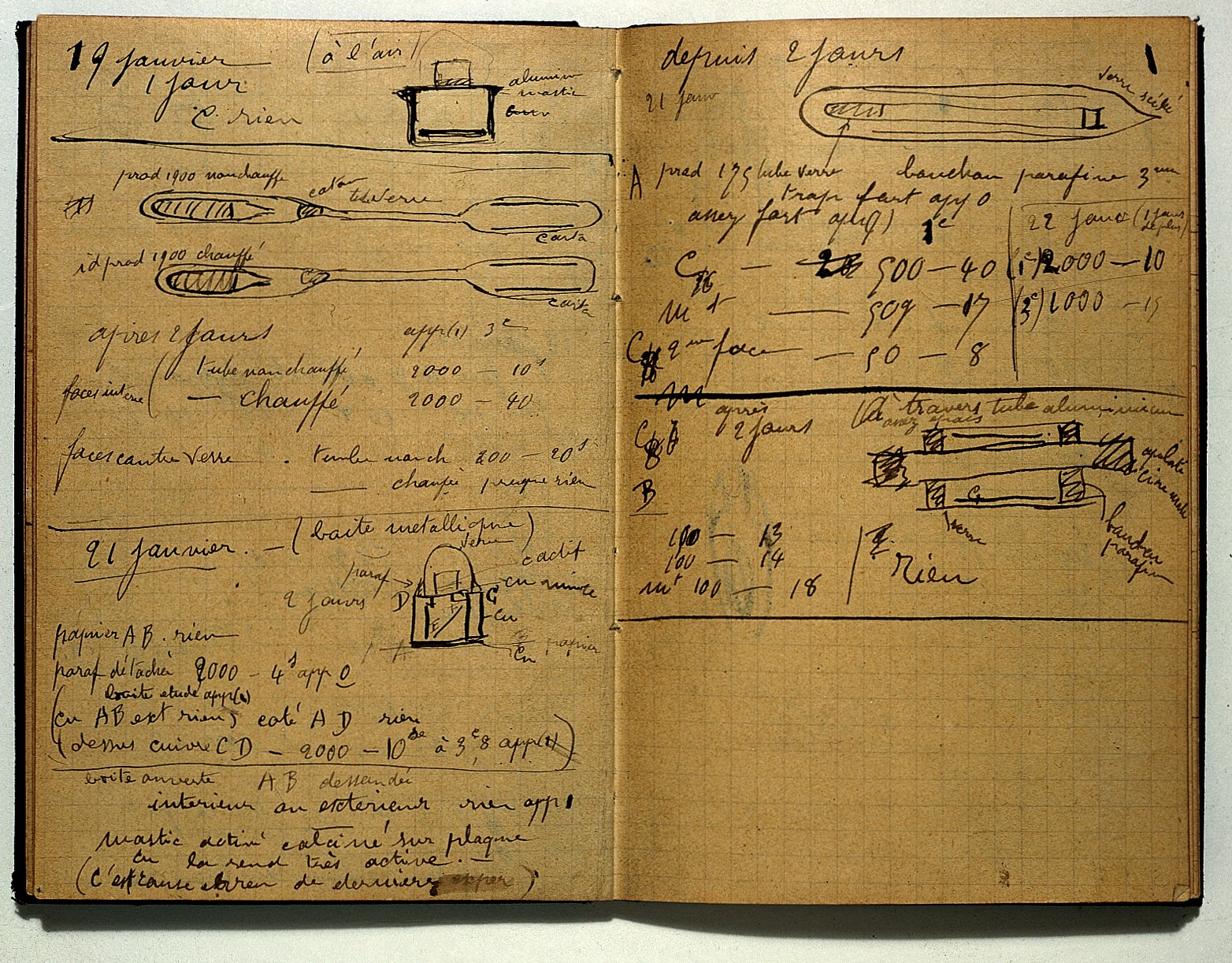

Radioactive notebook

As Lindsey Simcox writes, “When Marie Curie scribbled in her notebook, little did she know that many years later, physicists would need to assess the contamination from the radioactive material found in the binding.”[16]. This is an image of pages from the notebook of Marie Curie containing her notes and calculations on the subject of radioactivity [14,15]. The notebook is still radioactive as it is contaminated with Radium-226. It is one of her many objects that were contaminated with radioactive material.

In 1903, Marie Curie along with her husband Pierre and the physicist Henri Becquerel were awarded the Nobel prize in Physics for their pioneering work on the theory of “radioactivity”. Later, in 1911, she was awarded another Nobel prize, now in Chemistry, for discovering 2 new elements: Radium and Polonium, an element she name after her home country Poland. Marie Curie was also known for her modest and honest lifestyle, donating much of the Nobel prize money to friends, family, students and research associates, and also declining to patent the technology to isolate Radium, so that scientific progress could go ahead unhindered. [17, 18]

Since Radium-226 has a half-life of about 1600 years, the notebook will remain radioactive for many more years.

The renderings of a scientist-artist

Known as the father of modern neuroscience, Santiago Ramon y Cajal produced many such hand-drawings of neurons. This image is the drawing of neurons from pigeon cerebellum [19].

Much before he started his journey to pursue medicine, young Ramon y Cajal’s rebellious and anti-authoritarian attitude was a headache to many people around him [20,22]. In order to discipline him, his father (an anatomy professor) signed him up for making shoes and cutting hair. Ramon y Cajal wanted to become an artist to pursue his love for painting. One summer, his father took him to a graveyard to dig up human remains for anatomy study. Sketching bones pushed him into a new direction to pursue medicine. [20,23]

After moving to the university of Barcelona, he began his pioneering research on brain cells or neurons. At that time, the prevalent understanding was that unlike all other tissues in living things that are composed of individual units or cells, nervous system was instead a single continuous network (the reticular theory). Using Golgi’s cell straining method, which he further developed, and his artistic and aesthetic capabilities, Ramon y Cajal studied and sketched numerous brain cells, eventually concluding that the nervous system was not a single continuous network, but instead, was composed of individual units or cells, developing the neuron doctrine.

In 1906, Ramon y Cajal along with Golgi were awarded the Nobel prize in medicine in “recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system.”. Although known for his work in neuroscience, Ramon y Cajal did not give up on his childhood passion of art, which was a big part that lead to his scientific discovery too. A lesson to all of us in science who regularly work with data visualization, in what Erna Fiorentini calls ‘aesthetic epistemology’, – find that artist inside. [21]

Electrons and photons

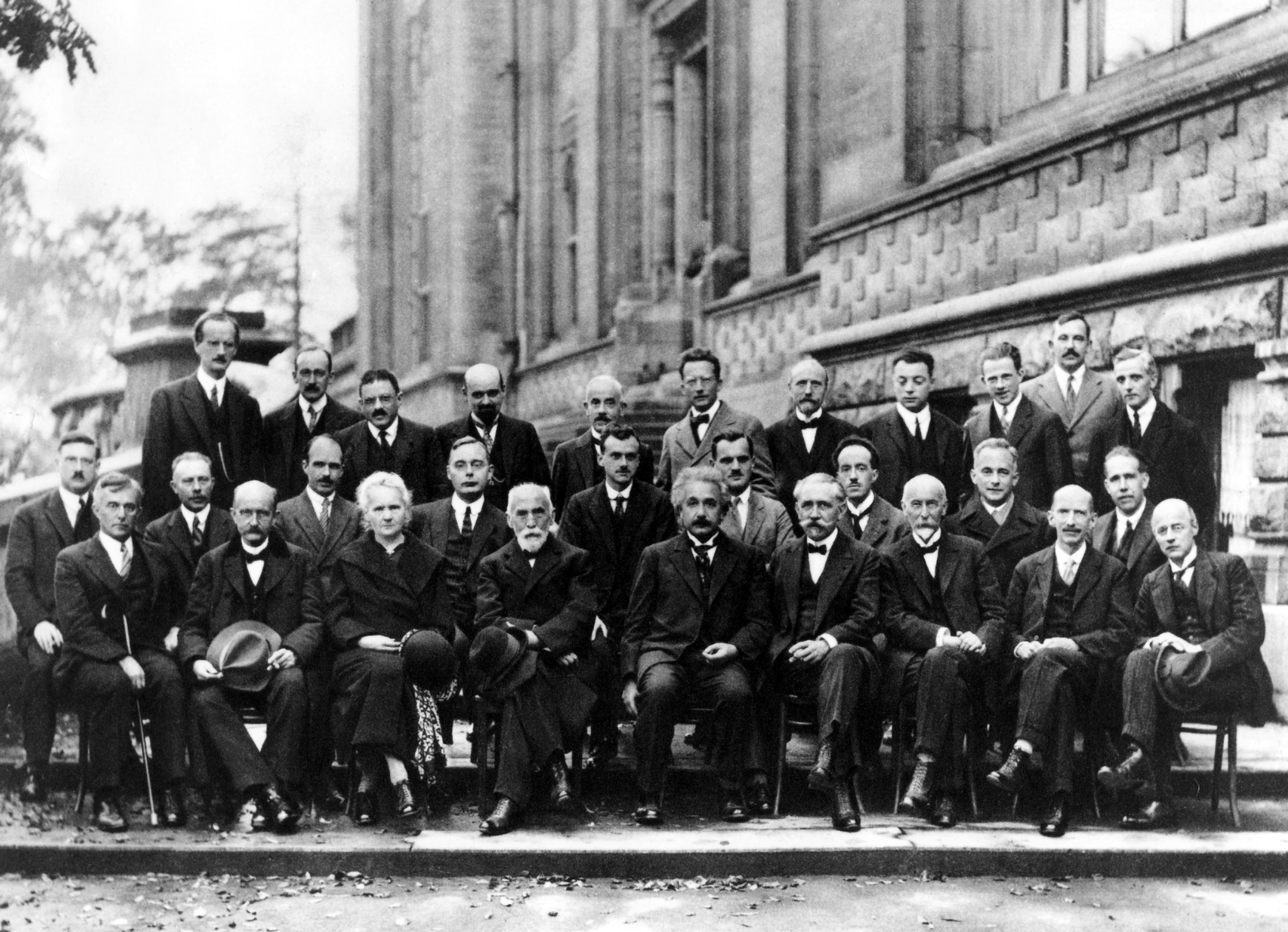

This image is of one of the most famous gatherings of scientists, the fifth Solvay conference (1927) in Belgium, with the subject ‘Electrons and Photons’, aimed to discuss the burning topic of the newly formulated quantum theory [24,25]. The meeting was attended by leading physicists and chemists of the time including Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Niels Bohr, Wolfgang Pauli, Sir Lawrence Bragg, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Max Planck, Louis de Broglie and many more. 17 of the 29 attendees became Nobel prize winners, including Marie Curie, who was the only women attendee and the only one who won 2 Nobel prizes in separate scientific disciplines.

One of my fondest memories growing up was watching the documentary Atom [26] narrated brilliantly by the physicist Jim Al-Khalili, where he talks so insightfully about this picture as follows:

“And over the week, the final showdown played out between Bohr and his arch-rival, Albert Einstein. Einstein hated quantum mechanics. Every morning he’d come to Bohr with an argument he felt picked a hole in the new theory. Bohr would go away, very disturbed, and think very hard about it, and by the end of the day he’d come back with a counter-argument that dismissed Einstein’s criticism. This happened day after day until by the end of the conference, Bohr had brushed aside all of Einstein’s criticisms and Bohr was regarded as having been victorious.

…

At the end of the conference, they all gathered for the team photo. Never before or since have so many great names of physics been together in one place. At the front, the elder statesman of physics, Hendrik Lorentz, flanked on either side by Madame Curie and Albert Einstein. Einstein’s looking rather glum because he’s lost the argument. Louis de Broglie has also failed to convince the delegates of his views. Victory goes to Niels Bohr. He’s feeling very pleased with himself. Next to him, one of the unsung heroes of quantum mechanics, the German Max Born who developed so much of the mathematics. And behind them, the two young disciples of Bohr, Heisenberg and Pauli. Pauli is looking rather smugly across as Schroedinger, a bit like the cat who’s got the milk.

This was the moment in physics when it all changed. The old guard was replaced by the new. Chance and probability became interwoven into the fabric of Nature itself and we could no longer describe atoms in terms of simple pictures but only using pure abstract mathematics.

The Copenhagen view had been victorious.

– Jim Al-Khalili, in the documentary “Atom” [26]

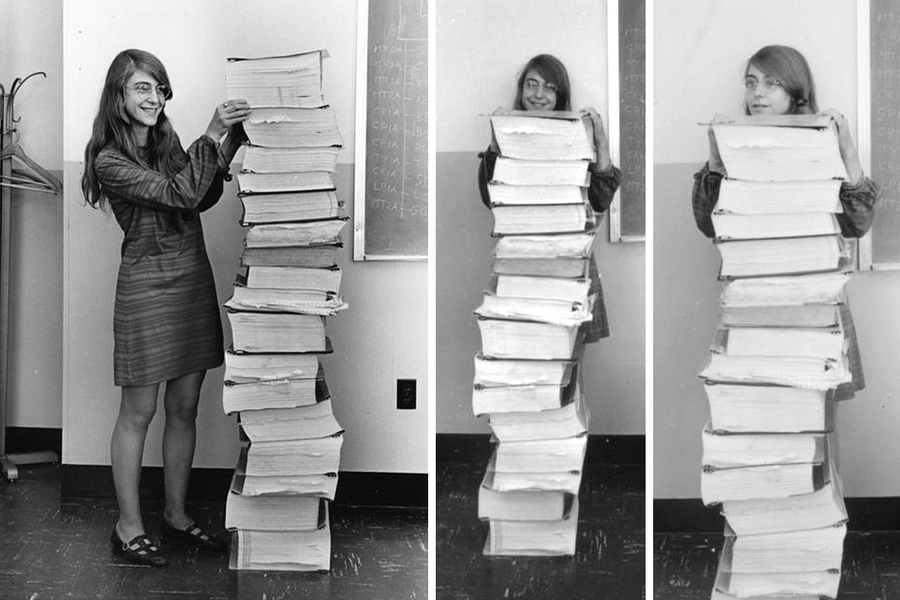

The code to land on the Moon

This photograph, unlike the others before it, is the famed picture from the world of technology rather than fundamental sciences. It shows Margaret Hamilton standing next to the software code that she and her team at MIT developed, which proved to be extremely critical for the success of the Apollo11 landing on the Moon and back to the Earth. [27]

Just as the landing module ‘Eagle’ of the Apollo 11 mission was about to reach the Moon’s surface, the astronauts started seeing warning messages. It was a go/no-go situation. The control room, with high trust in the software by Hamilton and team, asked the astronauts to go ahead. With only 30 seconds of fuel remaining, the Eagle module successfully landed on the lunar surface.

Hamilton’s priority display system was the key piece of software that helped in the successful landing. The Apollo guidance computer had access to only 72 kb of memory, which, compared to a 64 GB cellphone today, was about one million times less storage [28,29]. Therefore, the priority display system was key in warning about system overloads and about setting priority for more critical tasks than the ones that can be temporarily stopped.

Hamilton was a pioneer in software engineering – a term she coined herself. In her own words, “We took our work seriously, many of us beginning this journey while still in our 20s. Coming up with solutions and new ideas was an adventure. Dedication and commitment were a given. Mutual respect was across the board. Because software was a mystery, a black box, upper management gave us total freedom and trust. We had to find a way and we did. Looking back, we were the luckiest people in the world; there was no choice but to be pioneers; no time to be beginners.” [30]

I have seen my death!

The last image that I would like to share is more than a century old. It is an X-ray image known as “Hand mit Ringen” (Hand with ring) taken by Wilhelm Roentgen of the hand of his wife Anna Bertha Roentgen in 1895. According to legend, after seeing the image, she said, “I have seen my death!” and never set foot in his lab again [31,32]

Rontgen was working with cathode rays and testing their impact on a fluorescent screen on the recommendation of his colleague [33]. During these dark room experiments, he noticed that a barium platinocyanide coated screen far away from the experimental setup glowed as soon as he turned on the electricity. As he was not sure what these strange unknown rays were, he called them ‘X’ – rays, and decided to experiment with them systematically. Based on these experiments, along with discussions with his peers, he concluded that these were a new type of rays, which were similar to light, but highly energetic, such that they can pass through many objects (for e.g., human flesh).

Rontgen won the first Nobel prize in Physics in 1901 for discovering the X-rays. Realizing that these rays hold significant potential for medical applications, like Marie Curie, Rongten decided not to patent the technology to produce X-rays.

References

- Pale Blue Dot image credit: NASA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pale_Blue_Dot

- Sagan, Carl (1997). Pale Blue Dot. United States: Random House USA Inc. p. 6–7. ISBN 9780345376596.

- FRANKLIN, R., GOSLING, R.. Nature 171, 740–741 (1953).

- What Rosalind Franklin truly contributed to the discovery of DNA’s structure

- Watson, J. D. & Crick, F. H. C. Nature 171, 737–738 (1953).

- Wilkins, M. H. F., Stokes, A. R. & Wilson, H. R. Nature 171, 738–740 (1953).

- Crick, F. H. C. & Watson, J. D. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 223, 80–96 (1954).

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962. Nobel Prize Site for Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962.

- Bruce, J. Draft article on discovery of double helix, May 1953. Franklin Papers FRKN 6/4, Churchill College Cambridge, UK.

- https://science.nasa.gov/resource/close-up-view-of-astronauts-footprint-in-lunar-soil/

- Earth’s Moon – Apollo 11

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers

- L0021265 Marie Curie: Holograph Notebook. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

- https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cywqefw4

- https://blog.bir.org.uk/2015/09/02/the-radioactive-legacy-of-marie-curie/

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Curie

- Drawing of Purkinje cells (A) and granule cells (B) from pigeon cerebellum by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1899; Instituto Cajal, Madrid, Spain.

- Wiki: Santiago Ramon y Cajal

- https://towardsdatascience.com/aesthetic-epistemology-a-review-of-erna-fiorentinis-inducing-visibilities-3d61919593c3

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/happy-birthday-to-the-father-of-modern-neuroscience-who-wanted-to-be-an-artist-47241204/

- Finger, Stanley (2000). “Chapter 13: Santiago Ramón y Cajal. From nerve nets to neuron doctrine”. Minds behind the brain: A history of the pioneers and their discoveries. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 197–216. ISBN 0-19-508571-X.

- http://w3.pppl.gov/

- https://doi.org/10.3932/ethz-a-000046848

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1173021/

- https://news.mit.edu/2016/scene-at-mit-margaret-hamilton-apollo-code-0817

- https://gizmodo.com/the-computer-for-the-apollo-program-used-rope-memory-wo-5932207

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/margaret-hamilton-led-nasa-software-team-landed-astronauts-moon-180971575/

- https://news.mit.edu/2009/apollo-vign-0717

- The bones of a hand with a ring on one finger, viewed through x-ray. Photoprint from radiograph by W.K. Röntgen, 1895. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). Source: Wellcome Collection.

- X-Ray Anniversary

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/roentgen-xrays-discovery-radiographs

- https://bigthink.com/hard-science/10-science-photos-that-made-history/

- https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/science/scientific-insights/great-images-of-science/

Leave a comment