Ever since I watched the movie Mindwalk, I always wanted to visit Mont Saint Michel in Normandy, France. A trip to this beautiful tidal island transits via multiple cities and stops, and can take long if relying only on buses or trains. On the other hand, driving myself to Mont Saint Michel will save a lot of time, but the longest distance I ever drove until then was from Brussels to Côte d’Opale, France, a mere 230 km with our good old Ford Fiesta in 2023. And now that we switched to an electric vehicle (EV), Kia EV3, a relatively long road trip of about 600 km was not the first choice. The reasons were multifold, (1) this would be a long trip to drive all by myself, (2) EVs are still new, and any car malfunction will need specific expertise, meaning additional delays, (3) EV charging infrastructure in Europe is still in development and can result in us being stranded with no battery (range anxiety). Despite these practical challenges, as we will anyways need a car to move around to visit different cities within the Normandy region, we decided to do a proper planning on mapping the EV chargers, the highway stops we intended to make and drove to Mont Saint Michel.

Now that we’re back in Brussels after this lovely trip, I decided to write a short post about the things I learnt about going on a road trip with an EV, things that could have been done better, some unexpected (good/bad) experiences, and also a bit about the car itself, Kia EV3.

The car

Kia EV3 is a newly launched battery-EV (BEV), i.e., fully electric car without an internal combustion engine, and falls within the subcompact crossover SUV category. It has various versions with different upgrades, but the one we used is a front wheel drive (FWD), delivering an moderate output power of 150 kW or 201 hp. It has an 81.4 kWh NMC lithium-ion battery, which can provide a WLTP range of up to 600 km or 373 miles with 100% state of charge (SOC). However, this range drops in real case scenarios; more on this later in the post. It supports a maximum charging power (i.e., speed of charging) of 135 kW DC, and can charge from 10% to 80% SOC in about 35 to 40 minutes.

The planning

A proper planning is critical for an enhanced EV road trip experience. This could include planning the route, the highway stops that you wish to make, overlapping those stops with EV charging, pre-locating backup charging stations, preparing charging cards, apps and accounts, etc.

The apps

You may need 2 types of apps on your phone or in your car, (1) to locate the charging stations and (2) to use the charging stations. However, often, a single app can work for both the needs. To locate the EV chargers, I typically use one of the 4 options: A Better Route Planner (ABRP) or Chargemap or Kia’s in-built navigation system or Google Maps. I will now explain in detail the purpose of each of these apps.

- A Better Route Planner (ABRP): I use this app/website primarily to plan my route from origin to the destination, as this app is dedicatedly made for EVs, and can help you prepare a well-crafted route plan. The app can help you propose various highway rest stops, state of charge (SOC) on arrival for different destinations/stops, multiple plans to include your personal preferences such as many short stops or a few long stops or something in between. It also shows which charging stations have which type of charges, how many are available and the power of the available chargers. This app is ideal to be used a couple of days before the departure, to fix the route plan. Once the plan is ready, it can also be imported to Google Maps for navigation.

- Chargemap: I use this app on an everyday basis to quickly locate and check the availability of a nearby charger and to know the power of the charger. This app can also be used (in combination with a RFID card) to use the charging stations and to pay for the session. However, I currently have another charging card for this purpose.

- Kia’s in-built navigation system: This is usually my back-up in case something is wrong with Chargemap or ABRP.

- Google Maps: I typically use Google Maps either to navigate or to mark a specific charging station of interest. I have a personal list prepared Google Maps with the name “Chargers”, and I keep adding the stations of interest to this list. I have also made this list visible on the map, so I can easily visualize where the chargers of interest are located. This is particularly helpful for such road trips to avoid going back to ABRP or Chargemap to re-locate the chargers.

- Waze: I use Waze only for navigation purpose as the app is not particularly useful for including EV chargers in the plan.

The EV charging cards

In order to use an EV charging station, you typically need an RFID charging card. While it is possible to use a credit card or an app to purchase electricity for your session, this mode of payment is currently not readily available. Additionally, as there are many different suppliers/providers for charging stations, it can become difficult to keep 10 different charging cards. Therefore, a good solution to that is to use a multi-network access RFID card, such as Eneco or Chargemap. I used only Eneco charging card during this trip and I was able to use all the chargers on my route without any problem.

It may also be possible to charge your EV using just an app, however, I do not have any experience with this, so I cannot comment much about it.

The route

This step is not specific to EVs, but a general recommendation with all the vehicles. Whichever navigation app you prefer, Google Maps, Waze, the built-in navigation in your car, etc., planning a specific route of your choice will help you mentally prepare for the trip.

What matters more for an EV trip will be to plan a route with highway rest areas/stops that offer rapid EV charging, so you can plug-in your car while you take a break to eat, drink or rest; because not all the highway rest areas offer EV chargers. During this 600 km trip, I selected 4 highway rest areas (about every 150 km), with a 5th stop close to the destination, so that I can charge up the car to 90-100% SOC before checking-in the hotel; that way I am ready for the next day local trips to nearby towns. If the destination/hotel offers onsite charging, you can skip this last step. Rapid DC chargers also come in different powers (50 kW, 100kW, 150 kW, 300kW and so on). A higher power means that the charger can deliver more energy to the battery within a given time. However, as Kia EV3 has a maximum charging power of 135 kW DC, using any rapid charger that offers higher than 135 kW will be useless, as the car cannot charge faster. So I could use 100kW or 150kW and skip the 300 kW charger for others.

During these highway rest stops, I would quickly plugin my EV and go to grab a drink or something to eat or to the WC. Within these 15 to 30 mins of rest, the car would easily charge up to 70 to 90% SOC, before heading out again. This meant that when driving an EV, you do not need a significantly longer resting time to wait for your car to charge up, 15 to 30 mins are typical resting durations at such stops.

You will need charging stations not only when enroute to the destination but also at the destination if you plan to use your car for local drives. In the Normandy region, I found a limited number of EV charging stations. This was surprising as Mont Saint Michel is the most visited destination in France after Paris. However, even with the limited chargers, I was always able to find more than one available charging spot at any station or parking facility. This could mean that EV usage is extremely low in Normandy, such that the charging stations are almost always available.

This turns out to be a favorable situation for EV users, as we have dedicated charging spots reserved for EV charging, and even if a parking facility was full, I was easily able to find a spot to charge up my car. I believe that people who are switching to EVs at this moment, may find this situation to their advantage; however, we don’t know until when will this last. These spots must only be used for charging EVs and not for parking them.

Additional preparation recommendations

Below are a few additional preparation recommendations which may or may not be limited to EVs only and must be done at least a month in advance.

- Update yourself on the local traffic regulations of the destination. Depending on your destination, you may need an emission sticker/certificate/vignette, to be allowed to drive in restricted zones (such as low-emission zone (LEZ)). Online application for such stickers can take a couple of weeks for approval as well as delivery by post.

- Keep at least 2 EV charging cards with you, to avoid getting stuck and not being able to charge as you don’t have the right card. It is advisable to apply for a couple of multi-network RFID cards, so you can cover a large range of providers. Additionally, it is also recommended, to download the apps of these multi-network cards, and already create your accounts. This can also save you some time and unnecessary frustration.

- Use the “List” option in Google Maps to pre-mark multiple charging stations on your route as well as around the destination, so you can quickly locate the ones you may want to use.

EV charging etiquettes

- Parking an EV on an EV charging spot when you do not need charging are poor EV etiquettes and must be actively discouraged.

- Once your EV is fully charged, it is advised to move it so the next person can use the charging spot.

- When there is a queue for rapid charging, move your car as soon as you reach 80% SOC, as going from 80% to 100% SOC can take significantly long. It is generally recommended to charge up to 80% SOC and charge again at the next stop, as it will save you some time than waiting for 100% SOC.

- Use a charger with appropriate DC power, and leave the high-power charger for users who’s cars can accept high power.

- After completing your charging, leave the DC charging cable/plug back to its designated location/slot, and the charging area tidy.

I am a numbers guy –> Some data from my trip

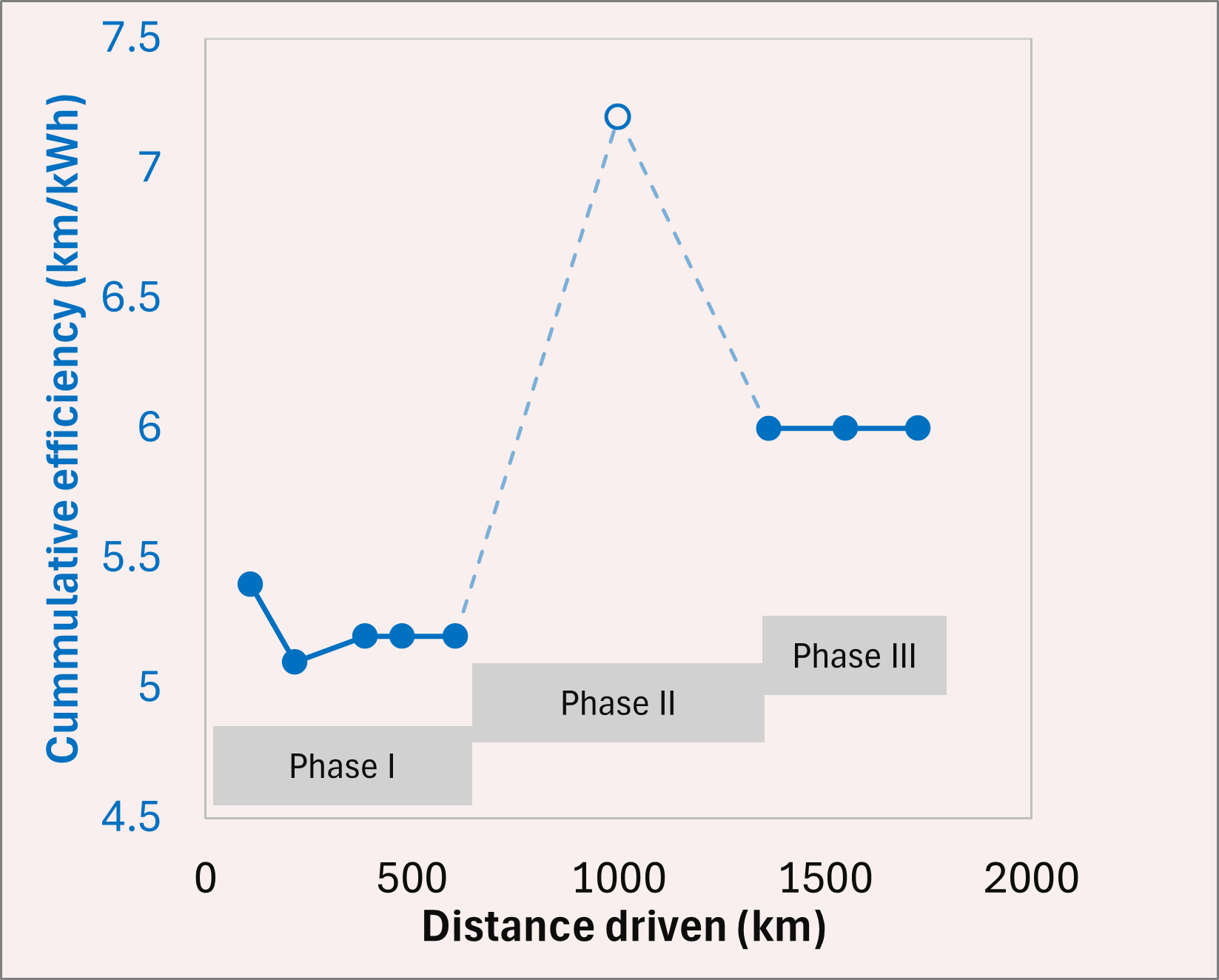

The efficiency of an EV is measured in the unit km/kWh, which means, how many km can an EV run per unit kWh of energy. They higher the better. In an ideal situation, the long-range model of Kia EV3 equipped with 81.4 kWh NMC lithium-ion battery, can provide a WLTP range of up to 600 km or 373 miles with 100% SOC. This implies that it has an efficiency of about 600 km / 81.4 kWh = 7.4 km/kWh, and can therefore run 7.4 km for a unit kWh of energy. Let see how this compares to real-case scenario. I drove the car in Eco mode with level 1 regen during this trip.

During this ~1700 km road trip,

- Phase I was driving from Brussels to Mont Saint Michel, 600 km on highways with a typical speed limit of 110 km/h and 130 km/h in France and 120 km/h in Belgium.

- In phase II, we then toured around Mont Saint Michel, visited a couple of cities and countryside in the neighborhood, headed to Etretat and also visited its neighboring towns. This was a mix of city drives, countryside drives and small patches of national and international highways covering a total distance of about 700 km, with speed limits ranging from 30 km/h up to 130 km/h.

- Finally, in the last phase III, we headed back to Brussels from Etretat, covering a distance of last 400 km on a highway with speed limit of 110 km/h and 130 km/h in France and 120 km/h in Belgium.

Based on driving distance covered and the battery used, Kia EV3 can calculate the real-time efficiency and average it over the driving distance, until reset manually. I recorded these efficiency values from the car during the phase I and phase III, the highway drives, but forgot to record during phase II. Therefore, as shown in figure 1, the cumulative efficiency, which continuously averages the efficiency throughout the drive, has solid circle data points (⬤) indicating the value recorded from the car. During phase I, the car efficiency averages at about 5.2 km/kWh, which mean that on highways, Kia EV3 can offer about 5.2 km/kWh x 80 kWh = 416 km of range with 100% SOC. This is 200 km short than the WLTP range of 600 km.

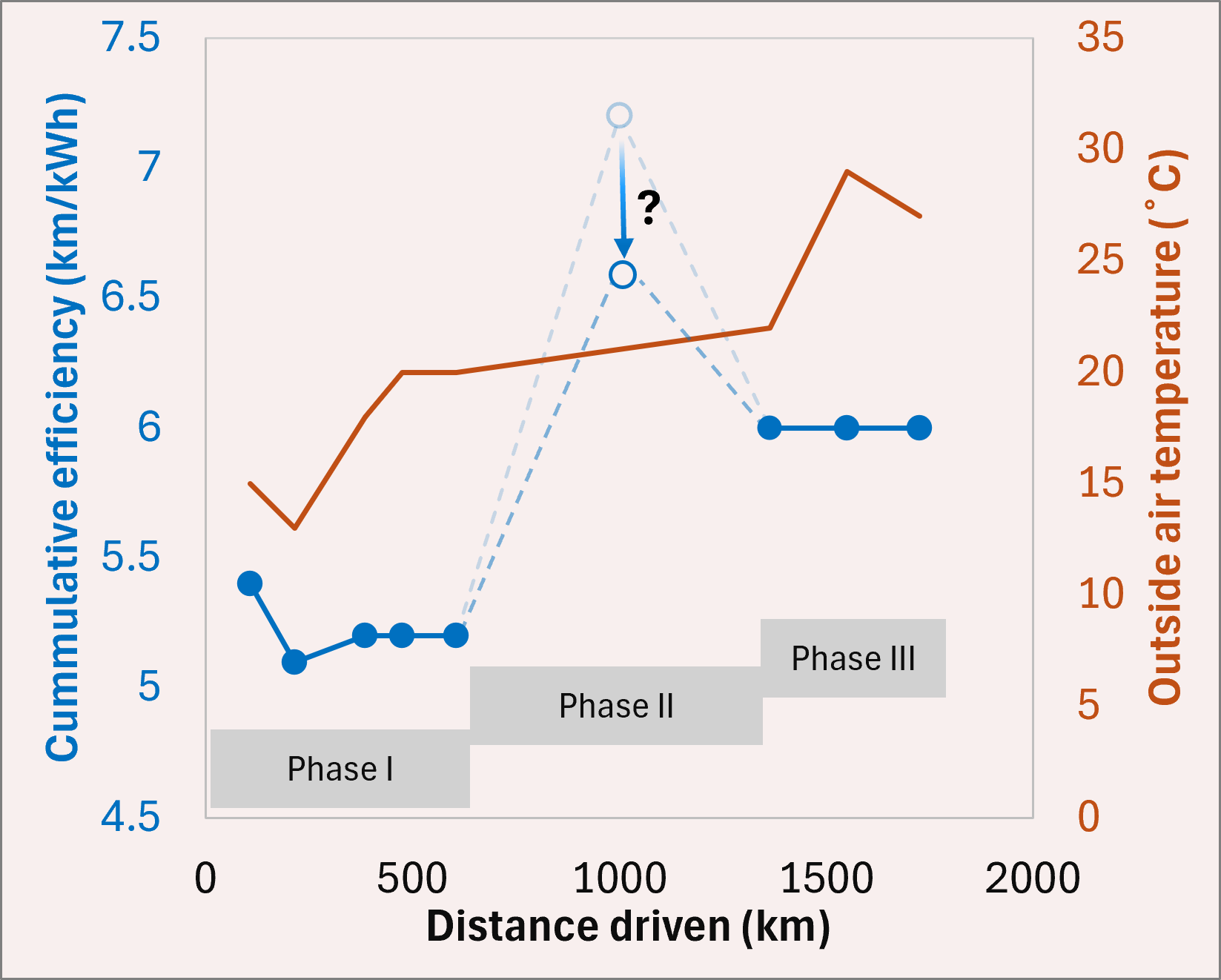

Let’s jump to phase III, which is again the highway phase. Interestingly, we observe a higher efficiency of about 6 km/kWh (i.e. 480 km range). This is because we are looking at cumulative efficiency and that is averaged over phase I + phase II + phase III. This means that phase II offered higher efficiency, such that phase III efficiency (although for a highway drive like phase I) increased up to 6 km/kWh. If we do a quick back of the envelop calculation, the phase II efficiency would be roughly around 7.2 km/kWh, i.e., a range of 576 km, pretty close to the advertised value. This hypothetical and calculated data point is represented as an open circle (◯) at 1000km distance in figure 1.

This was expected, as it is well known that unlike internal combustion engine vehicles that are powered by gasoline/petrol, EVs typically offer higher efficiency in cities (phase II) than on highways (phase I & III) [1],[2],[3].

However, only if calculating EV efficiency was that simple…

During the travel, it was observed that the atmospheric temperature kept on increasing day by day, and as we know, EV efficiency is battery temperature dependent [4][5], we may have to rethink the argument made for phase II. Below in figure 2, which includes additional data to figure 1, shows the atmospheric temperature while driving the car on those specific days, indicated with an orange line (—) and corresponding the values on the right-side Y-axis. As can be seen, the outside air temperature increased from 13°C to 20°C in phase I and up to 29°C during phase III. This could potentially explain the higher efficiency in phase III even though it was a highway drive. However, as was previously explained, it is well known that during city drives at lower speeds, EV efficiency is typically higher, therefore, we can still assume that in phase II the efficiency could still be as high as 6.7 km/kWh (based on my personal EV3 experience), which is a drop from 7.2 km/kWh (as shown in fig 2), after approximately taking into account the impact of increased atmosphere temperature.

I must caution that any phase II efficiency depiction in the figures is based on either simple back of the envelop calculations or just handwaving of numbers based on experience of my everyday home to work drive, which includes city + highway route.

The main idea behind these explanations is that EV range, which is a function of EV efficiency, depends on many factors (driving speed, driving mode, battery temperature, wind drag, regenerative breaking, use of air conditioning in the car etc). What must be noted is that with Kia EV3, obtaining a range of 600 km will be difficult, however, if you only have city drives or a mix of highway and city drives, you can get a range of about 450 to 530 km (depending on all other factors).

Conclusion

A 600 km road trip as a solo driver, followed by 1100 km more spread over the next 6 days, with an electric vehicle was a good experience. I must admit, initially, I was doubtful and concerned about the EV charging infrastructure and range anxiety, however, it was an enriching experience, and I learned a lot, which I am very happy to share in the form of this blog post.

Driving an EV for such distances is definitely not a concern, on the contrary, is in fact recommended (by me), and seeing from what many others have recorded and shared on YouTube, one can even drive further on.

Additional YouTube references to watch for fun

Leave a comment